Dear Christine,

I have two teenagers, a boy who is in high school and a girl who is in college. My daughter has always been self-motivated and a great student. I’ve never needed to nag her to do her homework, and she has always gotten good grades and great teacher comments.

My son is another story. His study skills are lacking. He doesn’t like school, and he doesn’t work very hard. I have to constantly be “on him” about his school work. We’ve had him tested for learning disabilities and ADHD, and he does not have either, although the tests showed that he does have great difficulty paying attention to things that he is not interested in.

He’s now a sophomore. Still, I’m constantly “helping” him with his homework, figuring out what work he has due, what tests he has coming up, or what assignments he might have failed to turn in. I’m afraid he won’t do it otherwise.

Our son says he does not want me to back off and that he wants me to continue helping him. At the same time, he is not exactly welcoming of my help in the moment. He’s often a little surly when I remind him of assignments, and he usually makes excuses for why he doesn’t have to work on something. He lacks self-motivation, and without me pushing him (and keeping him organized), I fear (1) that he might actually get worse grades; (2) that he won’t get a college degree; and (3) that this will limit his job prospects. Ultimately, I’m afraid that he’s going to end up living at home into his early adulthood, stuck on the couch playing video games.

I can’t help wishing that our son was more like our daughter. I want him to be more independent and self-motivated. Above all, I want him to do well enough in high school to go to a decent college. What do you recommend I do? If I’m honest, I’m looking for permission to keep propping our son up.

Thanks,

Parental Crutch

Dear Crutch,

So, it’s good that you have college and work aspirations for your son. But I’m afraid that your current efforts on his behalf aren’t going to pay off. Unfortunately, trying to control our children is frequently futile and usually counterproductive. In some ways, you are right to be worried: About a quarter of young men in the United States in their 20s are unemployed. That statistic is mind-blowing to the economists who track these things, given that men in their 20s have historically been the most reliably employed of any demographic. While the trend toward unemployment encompasses young men of all education levels, low-skilled men—like those without a college degree or training in a trade—are particularly likely to end up living back at home. A staggering 51 percent now live with their parents or another close relative. And what are they doing instead of working? (Hint: They aren’t going to school.) You’ve already guessed it; many of them are playing video games three or more hours a day.

That’s the clear conclusion psychologist Wendy Grolnick has reached over two decades of watching parents talk to their children. Here’s the gist of her research: The children of controlling parents—those who tell their children exactly what to do, and when to do it—don’t do as well as kids whose parents are involved and supportive without being bossy. Children of “directive” parents tend to be less creative and resourceful, less persistent when faced with a challenge, less successful at solving problems. They don’t like school as much, and they don’t achieve as much academically.

And what’s true for children in terms of parental control is about a thousand times more true about teenagers. Once kids reach adolescence, they need to start managing their own lives, and they know this. Most kids with micromanaging parents resist what their parents want for them every chance they get. They do this not because they are lazy or short-sighted, but because they need to regain a sense of control.

This cannot be overstated: Healthy, self-disciplined, motivated teenagers have a strong sense of control over their lives. A mountain of research demonstrates that agency—having the power to affect your own life—is one of the most important factors for both success and happiness. Believing that we can influence our own lives through our own efforts predicts practically all of the positive outcomes that we want for our teens: better health and longevity, lower use of drugs and alcohol, lower stress, higher emotional well-being, greater intrinsic motivation and self-discipline, improved academic performance, and even career success.

You have an important choice, Crutch.

Choice A: Keep riding your son; keep him organized and on track. He’ll likely get a lot more homework turned in, he’ll study for tests he would have avoided or forgotten about, and he’ll apply to the colleges you put in front of him. The big question in my mind, though, is about what will happen when he’s off at college and he doesn’t have you there by his side to keep him on track.

Actually, in my mind, it’s not that big of a question.

The odds are he won’t make it. An astounding 56 percent of students who start at a four-year college drop out before they’ve earned a degree. Nearly a third drop out after just the first year. If your son doesn’t develop the study skills he needs to succeed (without you), he is not likely to develop them once he gets to college.

Which brings us to Choice B: Back off so that your son can build the skills he’ll need to survive without you. This does mean risking letting your son stumble, but at least he’ll be at home with you when he does.

Your son, of course, will not want you to back off. Why would he want to put in that kind of effort if you’ll do it for him? Plus, there is no risk for him right now; he can’t really fail if he doesn’t really try.

I’m not saying disengage from his life. It’s important for you to stay involved and supportive, but to do so without being directive or controlling. Set limits so that he knows you aren’t lowering your expectations. For example, if you expect him to maintain a B average, that’s great. What happens if he doesn’t do that? Decide as a family, and then be firm and consistent in enforcing your limits.

In fact, don’t dial back your effort at all, just shift your focus. Right now, you are propping your son up. Instead of putting all your energy into doing things that your son would be better off doing for himself, put your effort into supporting his self-motivation.

As I explained not long ago to another mom who was overhelping her husband, the way to foster self-motivation in others is to support their autonomy, their competence, and their relatedness. These are the three core psychological needs that, when filled, lead to self-motivation. You can choose to refocus your attention on promoting his self-motivation. Here’s how.

1. Give him more freedom.

He needs the freedom to fail on his own—and the freedom to succeed without having to give you credit. Your son can’t feel autonomous in his schoolwork if you are still the organizing force.

Instead of directing your son, ask him: “What’s your plan?” As in, “What’s your plan for getting your homework done this weekend?” Asking kids what their plan is makes it clear that they are still in control of their own behavior, and it helps put them in touch with their own motivations and intentions. Often kids simply need to make a plan—and sometimes if they aren’t asked to articulate their plan, they won’t make one. (Especially kids who are used to being nagged; those kids know that their parents will eventually get frustrated and do their planning for them.)

This not-making-a-plan thing is developmental, by the way—it is often more about their executive function than their motivation. Our frontal lobe, which enables us to make plans for the future, often doesn’t develop fully until our mid-20s. This doesn’t mean that teenagers can’t plan, or that we should do it for them; it just means that they need a little more support practicing planning than might be obvious given their other capabilities.

It’s also really important that we parents pay close attention to our tone of voice, especially if what we are saying could potentially limit our kids’ freedom in some way—if we are making a request that could be interpreted as pressure. Research suggests that moms who talk to their teens in a “controlling tone of voice” don’t tend to get a positive response, and they are more likely to start an argument.

It’s not enough to just stay neutral, unfortunately; although a neutral tone of voice is less likely to make teens defensive and argumentative, it was found to be equally ineffective in motivating kids.

What did work? The teens who were the most likely to carry out the request being made had parents who used a “supportive” and encouraging tone of voice.

2. Help him feel more competent.

If I were a betting woman, I’d bet that your son feels incompetent compared to his superstar sister. This likely leads to resignation. Why should he try if he’ll never be as good as her, anyway?

Help him see where he’s done really well in the past through his own effort (rather than your nagging). Don’t be afraid to ask him: Where do you feel most confident? And then help him see that it is his own effort that has led to that capability.

You can also support him in building new competencies. It sounds like he needs to build better study skills, for example. Who would be a good study skills coach for him? It’s important for him to develop his ability to learn and push himself outside of his comfort zone.

3. Finally, support his sense of belonging and connectedness with others, particularly at school.

Is there a teacher whom he feels connected to who can encourage him? Or a coach who is also willing to talk to him about his life as a student? Or a peer group who would encourage him to pay more attention to school work? Sometimes the best way we can help our kids is to help them find a community where they can thrive. One way to do this is to enlist the interest and attention of another adult.

Crutch, I’m very clear about this: The time to take the training wheels off is now. When he falls, let him pick himself up and try again. This will build autonomy and competence. You can celebrate his successes—this will build relatedness. Let him learn how to ask for the help he needs; when he gets it, it will expand his sense of belonging and connection to others.

Redirecting your energy towards promoting your son’s self-motivation will not likely be in your comfort zone. But once you get the hang of not nagging and not being so directive, your relationship with your son is sure to be far more rewarding—for you both.

Yours,

Christine

MORE ON RAISING HAPPY TEENS

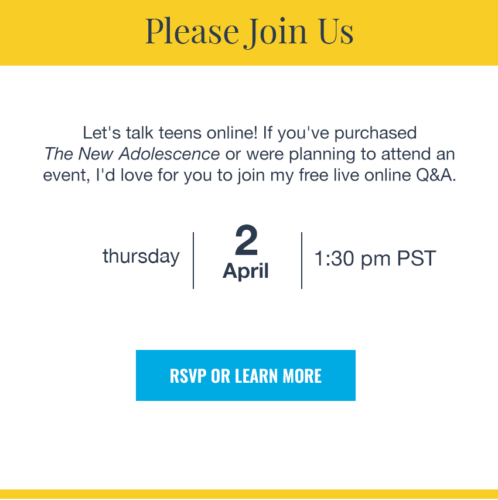

If you like this post, I think you’ll love my new book, The New Adolescence: Raising Happy and Successful Teens in an Age of Anxiety and Distraction.

If you’re in the Bay Area, we hope you’ll join us for the launch at the Hillside Club on February 20, 20! Find more information about my book events here.

These thoughts occur because many teenagers tend to be either terribly disorganized, requiring constant nagging, or tightly wound, perfectionistic, and in need of constant therapy. There’s also all that new neuroscience showing, unfortunately, that the brain regions that help humans make wise choices don’t mature until kids are in their mid 20s, and that many potentially life-threatening risks become more appealing during adolescence while the normal fear of danger is temporarily suppressed. Knowing these things can make it hard for us parents to relax.

These thoughts occur because many teenagers tend to be either terribly disorganized, requiring constant nagging, or tightly wound, perfectionistic, and in need of constant therapy. There’s also all that new neuroscience showing, unfortunately, that the brain regions that help humans make wise choices don’t mature until kids are in their mid 20s, and that many potentially life-threatening risks become more appealing during adolescence while the normal fear of danger is temporarily suppressed. Knowing these things can make it hard for us parents to relax.