Last autumn, horrific wildfires raged near our home. People we knew were losing their houses left and right. In the midst of disaster, I had to leave town for work.

To make myself feel better, I typed up three single-spaced pages of detailed instructions for what my family should do in case of fire or earthquake. Which I then laminated. And posted in each of my kids’ bedrooms.

I then made my family practice an emergency evacuation. Tanner, age 15, volunteered to take care of the family heirlooms. I drilled him, dead serious: “Which are the high-priority photo albums?” Molly, 14, was drawing on her ankle with a ballpoint pen. “Molly! Pay attention! When you get Buster into the car, what else do you need to make sure you have with you?”

My husband rolled his eyes.

Until recently, I’d thought that I’d more or less conquered perfectionism. Perfectionism, I’d become fond of saying, is a particular form of unhappiness. I’d thank GOD I wasn’t a perfectionist anymore.

Hah.

While it is true that I am no longer as afraid of making mistakes or disappointing others as I was in my youth, I have obviously not yet rid myself of perfectionism. I’ve just turned it outward, to the world, and especially to others. How am I trying to solve this problem of mine? Read on.

Inner turbulence, outer control

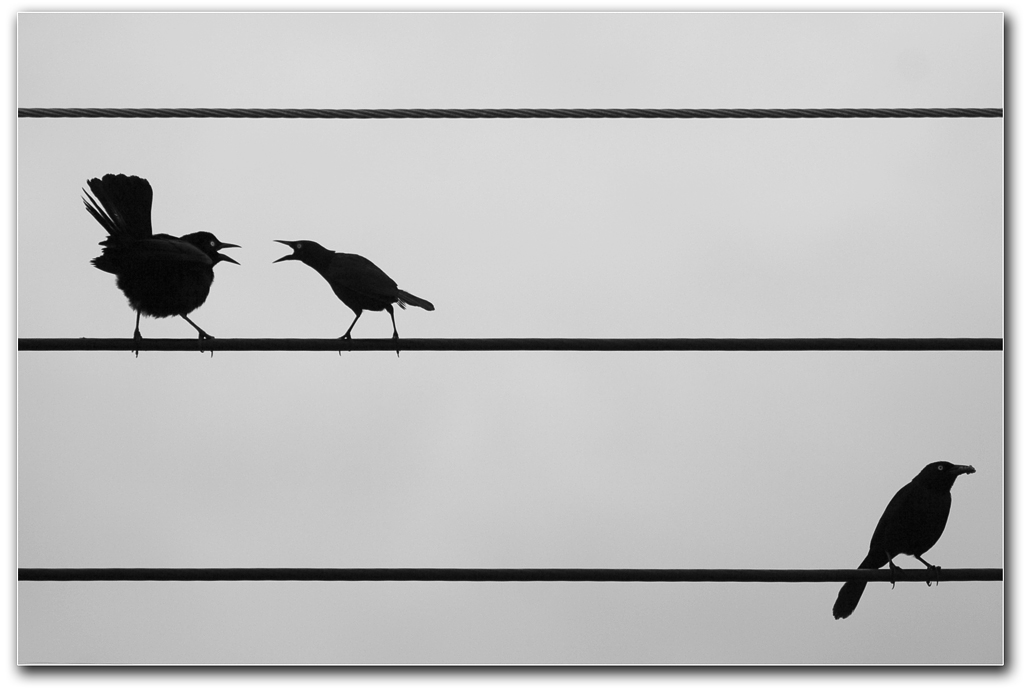

The more turbulent I am inside, the more I try to control what’s happening outside. Some people look away when chaos reigns; I dig in. I boss people around. I am aggressive about what I think is right.

Feeling like I am right, like I know what to do, delivers a hit of certainty in a world of unending and catastrophic natural disasters, in a country where mass shootings are commonplace and our hot-headed president brags about his ability to start a nuclear war.

But every time I try to control anything other than my own thoughts—the weather, my husband, my children—I’m sending a message to the world and the people around me that they are not good enough. This absolutely is perfectionism, and indeed, it is a particular form of unhappiness—one that spreads like wildfire.

This control freakish-ness indicates that I have problem with what researchers call “other-oriented perfectionism.”

I’m not alone. A new study published in Psychological Bulletin demonstrates that perfectionism is increasing over time: Today’s youth are more demanding of others, and they are more demanding of themselves. They also feel like other people (e.g., parents like me) are more demanding of them.

Like its close cousins “self-oriented perfectionism” and “socially prescribed perfectionism,” other-oriented perfectionism leads to nothing good. Although we often think that perfectionism is a cause of success—“I’m a bit of a perfectionist” is a socially acceptable humble-brag—research clearly demonstrates that perfectionism is often debilitating. A well-studied phenomenon, perfectionism is clearly associated with serious depression, chronic anxiety, and myriad health problems.

And “other-oriented perfectionism” comes with additional drawbacks: In intimate relationships, it is linked with “greater conflict and lower sexual satisfaction.” When I get bossy and controlling, the people around me feel defensive, or they feel wrong, or they feel a lack of control—nothing anyone ever wants to feel.

Being controlling is like a sugar rush: It might bring me a quick hit of tense certainty, but never lasting peace. This is because all control is false. Temporary at best. Life is inherently uncertain. We might hate that, but it’s true. We can be sure of only one thing: We will die. And we are usually not even in control of that.

How to surrender

Given this, why do I so consistently and diligently resist uncertainty by trying to get the world to do things my way? And what can I do instead of retreating back into perfectionism?

The opposite of perfectionism is acceptance. Not resignation, but surrender…to whatever is happening in the present moment. I know, I know: That sounds terrible to my fellow control freaks. Bear with me.

You may have heard the truism that what we resist, persists. This teaches us that we often prolong pain and difficulty through resistance. Perfectionism is a form of resistance to whatever is actually happening in the present moment. At its foundation, it is a rejection of the current reality.

Research by Kristin Neff and others shows that resistance increases our suffering, while acceptance—particularly self-acceptance—is one of the lesser-known secrets to happiness.

But this idea that we do better when we don’t resist difficulty is very counterintuitive. How do we even begin to stop resisting what hurts or what scares us?

Behavioral science and great wisdom traditions both point us towards acceptance. It is strangely effective to simply accept that which we cannot control, especially if we are in a difficult or painful situation. To do this, we accept the situation, and also our emotions about the situation.

Instead of laminating instructions for exactly what to do during a disaster (because, you know, when the house is on fire that’s just what everyone needs), I could have let myself accept reality: We could, at some point, lose our home in a fire. And then I could just let myself feel the fear and anxiety I was actually already feeling.

This approach requires trust. Trust that if I’m still here, still breathing, everything is okay. Trust that even if I don’t give specific instructions, if I back off from trying to control everyone and everything, life will continue to unfold just as it’s meant to. Trust that even if it all goes to hell, even if other people make mistakes or do things differently than I would do them, that I can deal with the outcome, no matter what it is. Trust that I can handle all the difficult emotions that come up in response to what does or does not happen. Trust that I can handle loss and grief should it come.

“You know what to do now, in a fire or an earthquake?” I asked the kids a few weeks later.

“Pretty much,” Molly answered, looking up.

“What?” I asked.

“Depends what we’re dealing with. I’m in charge of Buster. I’ll get him to the meeting place.”

This is a good-enough plan…even though it does not account for some critical details.

Weirdly, this trust and acceptance thing works. When we suppress or deny our emotions (or distract ourselves from them by writing and laminating instruction manuals), they don’t actually go away. In fact, they tend to generate an even bigger physiological response, which makes us more, not less, anxious. But when we let ourselves feel what we feel, we can process what is happening for us. We don’t feel fewer challenging emotions, but we do feel them for less time.

For example, we might have a particularly difficult relationship with a neighbor or in-law. We can accept this as our reality, and also that we feel frustrated and saddened by the situation. This doesn’t mean that the situation will never get better; acceptance is not the same as resignation. We can work to make the relationship less difficult (or to be reasonably prepared in the event of a disaster), while at the same time accepting the reality that the relationship is very difficult. Maybe it will get better—and maybe it won’t.

Accepting the reality of a difficult or scary situation and our limited control allows us to soften. And this softening opens the door to our own compassion and wisdom.

And in this crazy and uncertain life, we human beings need those things.