Screen time is a likely cause of the ongoing surge in teen depression, anxiety, and suicide.

Some days, I can see how profoundly anti-social technology makes my family, adults and teens alike. We joke that our kids get “screen stoned”—spacey and despondent, or irritable and aggressive. We may laugh, but it isn’t that funny. I know what all that screen stimulation is doing to my teenagers’ brains, and it’s concerning.

I know I’m not alone in worrying; half of parents surveyed in 2018 said that they were concerned that their “child’s mobile device use is negatively affecting his or her mental health,” and nearly half thought their child was addicted to the device.

Here is what we know: The spike in the amount of time teenagers spend on screens is a likely cause of the ongoing surge in depression, anxiety, and suicide that began shortly after smartphones and tablets became widespread among teenagers, around 2012. By analyzing multiple data sets—all large-scale, long-term scientific studies, not one-off surveys—demographer and psychologist Jean Twenge has clearly shown that American teens who spend more time online are more likely to have at least one outcome related to suicide, like depression or making a suicide plan.

The numbers are enormous: Nearly half of teens who indicated that they spend five or more hours a day on a device (like a phone or laptop) said they had contemplated, planned, or attempted suicide at least once—compared with 28 percent of those who have less than an hour of screen time a day.

Twenge, who has analyzed the data more closely than anyone, writes that “the results could not be clearer: Teens who spend more time on screen activities are more likely to be unhappy, and those who spend more time on nonscreen activities are more likely to be happy.” Obviously, there is a toxicity to screen time—although not everyone agrees with this message.

The smartphone controversy

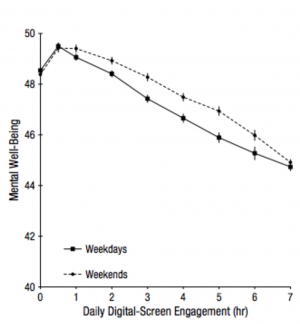

All the research I’ve seen on new media and teens indicates, in one way or another, that there does in fact seem to be a “dosage effect.” Some smartphone use, for example, is totally fine, but after a certain point it can become toxic.

And yet sometimes even the researchers themselves deny this toxicity. For example, Candice Odgers, a psychologist at the University of California-Irvine, wrote in Greater Goodmagazine recently that “there is no compelling evidence that spending time online has a deleterious effect on teens’ mental health.” I was surprised by this, and so I took a look at the large-scale study published in Psychological Science in 2017 that she references.

It was loaded with evidence that spending a lot of time online is correlated with lower well-being in 15 year olds. As you can see from the graph, taken directly from the study, the more “daily digital screen engagement” (here, that’s smartphone use), the lower the teen’s mental well-being (which includes how happy, connected, resilient, and self-confident they feel). The relationship is very clear, and very linear: After a little less than an hour a day of time spent on a smartphone, their well-being begins to decrease.

Doubters are quick to suggest that depression may cause teens to spend more time online rather than the other way around. But Twenge and other researchers have considered that possibility, and they hold that it just isn’t the case.

For one thing, a fair bit of research suggests that screen time (especially social media usage) leads to unhappiness. For example, there are several studies that have all found basically the same thing: The more people use Facebook, the lower their happiness (and the higher their loneliness and depression) when researchers assess them again later. It wasn’t that people who were feeling unhappy used social media more; it’s that Facebook likely caused their unhappiness.

The other thing is the timing of it all; if feeling depressed causes people to spend more time on their devices and not the other way around, then why did depression and suicidality increase so suddenly after 2012, when smartphones became much more widespread? “Under that scenario,” says Twenge, “more teens became depressed for an unknown reason and then started buying smartphones—an idea that defies logic.”

Logic-defying or not, the idea that unlimited technology use is not harmful will always have its staunch defenders. “Drawing a causal link from such correlational evidence requires a bit of a leap,” Peter Etchells, a lecturer at Bath Spa University, told Wiredmagazine:

You’d never be able to account for all the factors that might impact on things like depression and suicide, so you can’t say definitively that, if social media goes up over a period of five years and depression and suicide go up over a period of five years, one is causing the other.

Etchells posits that people are becoming more open to talking about their experiences with depression and suicide, and so they are more likely to report them to researchers. But this reasoning still doesn’t explain the twin spikes in screen time and angst. Surely a hypothetical shift in attitudes toward talking about depression wouldn’t show up as the largest mental health crisis we have ever seen.

When we resist the idea that new technologies can be harmful, we rule out a more full understanding of their toxicity. And if we don’t understand how they are shaping us and our kids, we can’t adapt to them in healthy ways.

This post originally appeared on The Greater Good Science Center

This post originally appeared on The Greater Good Science Center