This post is from a series about the ideal worker archetype in my online course, Science of Finding Flow. Read the rest here.

I don’t know anyone who has worked for a traditional business who hasn’t run up against our cultural notion of what journalist Brigid Schulte calls “the ideal worker” — the perfect employee who, without the distractions of children or family or, well, life, can work as many hours as the employer needs.

Ideal workers don’t have hobbies — or even interests — that interfere with work, and they have someone else (usually a wife) to stay home with sick children, schedule carpools, and find decent child care. Babies aren’t their responsibility, so parental leave when an infant is born isn’t an issue; someone else will do that. The ideal worker can jump on a plane and leave town anytime for business because someone else is doing the school pickups, making dinner, and putting the children to bed. They call meetings at 7:50 in the morning, making sure anyone with kids feels stressed and deficient when they don’t want to get their kids to school an hour early.

Unfortunately, honing that one strength won’t get us very far. Why? The ideal worker is not necessarily ideal. Reams of research suggest that people who work long hours, to the detriment of their personal lives, are not more productive or successful than people who work shorter hours so they can have families and develop interests outside of work. Shulte reports:

The United States works among the longest hours of any advanced economy, but it is not the most productive per hour. That efficiency goes to countries like Norway. Economists like Stanford’s John Pencavel have found a “productivity cliff.” Productivity drops steeply after a 50-hour work week, and drops off a cliff after 55 hours. Exhausted employees are not only unproductive, but they are also more prone to costly “errors, accidents, and sickness.” “Is it possible,” Pencavel wrote, “that employers were unaware that hours could be reduced without loss of output?”

So why do we continue to believe that the longer and harder we work, the better we’ll be?

The ideal worker archetype was born more than 200 years ago during the Industrial Revolution. The rise of the factory system in the late 18th century marked the first time that a clock was used to synchronize labor. Once hours worked could be quantified financially, people developed a new perception of time, one that saw the amount of time on the job as equivalent to a worker’s productivity.

...people who work long hours are not more productive or successful than people who work shorter hours. Share on XDo you think that “Time is Money?” Are you suuuuuure? In our next installment of “The Science of Finding Flow,” we’ll learn why this notion no longer holds true.

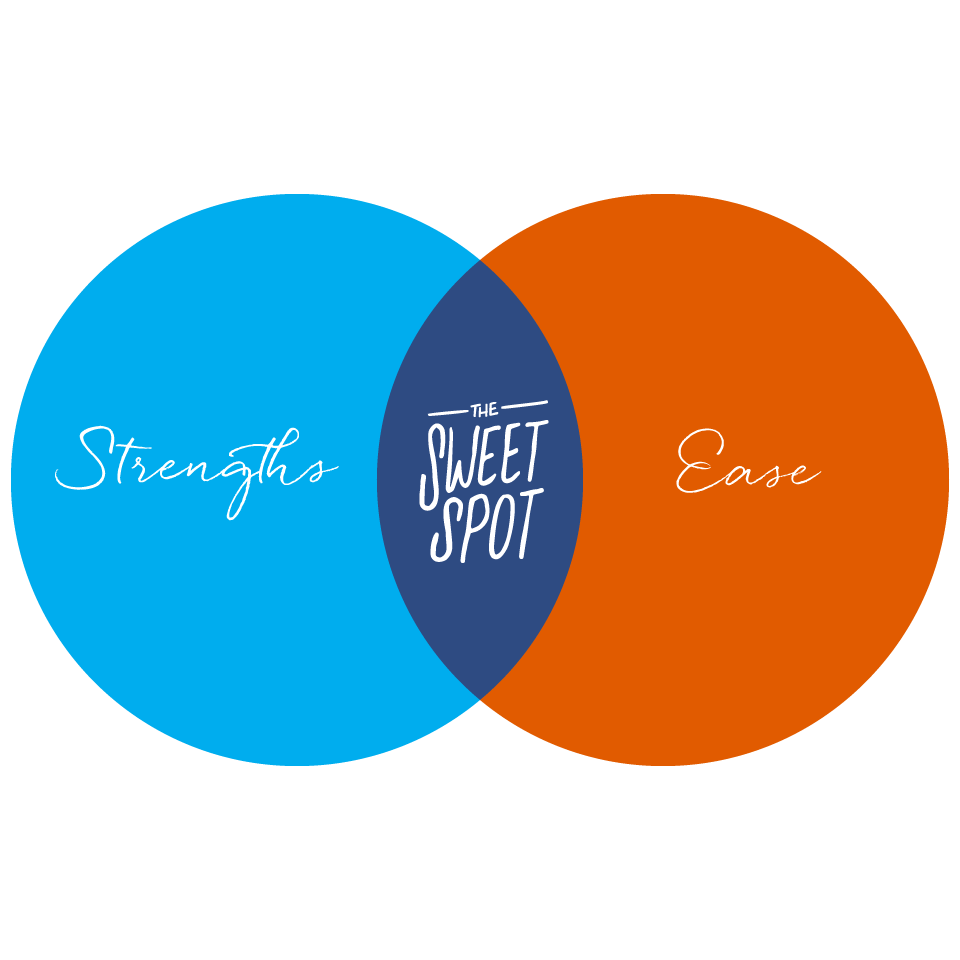

This post is taken from “The Science of Finding Flow,” an online course I created as a companion to my book The Sweet Spot: How to Accomplish More by Doing Less. I’m sharing one “lesson” from this online class per week here, on my blog. Want to see previous posts? Just click this The Science of Finding Flow tag. Enjoy!

![A society grows great when old [people] plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in. - Greek Proverb -](https://www.christinecarter.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/christine_carter_thursday_thought_greek_proverb.png)